In my last blog I said that in my next blog I would focus on the Indus Valley civilization. However, I have delayed that blog in order to provide my reactions to an article that concludes there is no real evidence that Africans and/or Egyptians ever made it to the Americas prior to Columbus’ voyage in 1492.

In creating the African and Egyptian influences blog on Olmec civilization, I used a number of sources including Dr. Ivan Van Sertima’s book “They Came Before Columbus (TCBC).”

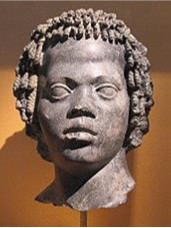

Olmec Head

In November of 2020, a reader of my Olmec Civilization blog wrote me asking for my reaction to “Robbing Native American Culture” (RNAC) written in 1997 by Dr. Gabriel Haslip-Viera, Dr. Bernard Ortiz de Montellano, and Dr. Warren Barbour that seeks to discredit Dr. Van Sertima’s book TCBC. RNAC says Dr. Van Sertima’s work fails to make a solid case for the following reasons:

1. No genuine African artifact has ever been found in a controlled archaeological excavation in the New World.

2. The presence of African origin plants such as the bottle gourd … or of African genes in New World cotton” … shows “there was contact between the Old World and the New, but this contact occurred too long ago to have involved any human agency.” As for maize, it “was brought by the Portuguese from the West Indies … to the coast (where it had been unknown) and to other parts of Africa after a.d. 1550.” (RNAC p. 430)

3. The colossal Olmec heads, which resemble a stereotypical ‘‘Negroid,’’ were carved hundreds of years before the arrival of the presumed models.

4. Nubians, who come from a desert environment-and have long, high noses, do not resemble their supposed ‘‘portraits.’’

5. Claims for the diffusion of pyramid building and mummification are fallacious.

In short, RNAC claims Dr. Van Sertima provides no real evidence that Africans and/or Egyptians ever made it to the Americas prior to Columbus’ voyage in 1492.

In response, I did more research and created this extension of the Olmec blog that contains the following evidence and responses to the five RNAC assertions.

Assertion 1 – No Genuine African artifacts found in the new world

• Response 1 – This assertion in RNAC does not mention African skeletal remains at two archeological Olmec sites, Tlatilco and Cerro de las Mesas. Tlatilco was a large pre-Columbian village near the modern-day town of the same name in Mexico and flourished between 1200 BCE to 200 BCE. Cerro de las Mesas is an archaeological site in Veracruz Mexico, and was a prominent regional center from 600 BCE to 900 CE.

Dr. Andrzej Wiercinski found some of the Olmec skeletons at Tlatilco and Cerro de las Mesas were of African origin. Another person, R.A. Jairazbhoy, an archeologist whose work was cited in RNAC, is said to have examined Dr. Wiercinski’s work and found that 13.5 percent of the Tlatilco skeletons were of Africans and 4.5 percent of the Cerro skeletons were of Africans. This suggests that over time the African population gradually fused with the Native American population.

Assertion 2 – “The presence of African origin plants” …. was “too long ago to have involved any human agency.” The focus is on “cotton, the bottle gourd, and maize.”

• Assertion 2a Bottle Gourd – “If a gourd on its arrival in the New World was tossed up on the beach by a storm and broken so that the seeds could escape or picked up by a curious person and transported inland, the gourd would spread.” (RNAC p. 430)

• Response 2a – On pages 206 and 207 of Dr. Van Sertima’s book, it says most “botanists hold that the bottle gourd was introduced into the Americas by natural drift across the ocean.” Dr. Van Sertima then asks “If it is true that African gourds simply got lost and drifted westward until they hit the American mainland, why did they never appear in cultivation along the waterfront or littoral, but only far inland?” While this is a question worth answering, it does not make human agency a condition of his theory.

• Assertion 2b Cotton – “The time involved in forming hybrids and subsequently diffusing these tetraploid species as widely as they are found means that the time of initial hybridization was thousands of years prior to Van Sertima’s postulated 4th millennium-B.C. drift voyage.” (RNAC p. 430)

• Response 2b – Dr. Van Sertima states that the African diploid cotton could not have drifted by itself across the ocean but had to come to the New World via human transport most likely from Africa. The RNAC discounts the possibility of a human agent in transporting the African cotton to the Americas. The RNAC also discusses research that cites the Killdeer, a bird, that can retain cotton seeds in their guts for several days without loss of seed viability. However, the migratory patterns of the Killdeer are limited to the Americas. Warblers fly thousands of miles across the Atlantic, but their journey requires them to “first pack on the pounds, then absorb their intestines, and finally forgo eating and sleeping for three days. Hence, they cannot be the source of the introduction of the African cotton in the Americas. This leaves Dr. Van Sertima’s human intervention theory still very viable.

• Assertion 2c Maize – “(M)aize was brought by the Portuguese from the West Indies to São Tomē and then transmitted to the coast (where it had been unknown) and to other parts of Africa after A.D. 1550.” (RNAC p. 430)

• Response 2c – An article entitled Pre-Columbian Maize in Southern Africa dated August 12, 1967 in Nature, by M.D.W. Jeffreys of the University of Witwatersrand provides evidence for the presence of maize in southern Africa. He states the inland “Bantu from the north acquired maize long before da Gama had reached Mozambique in 1498 and before Columbus was born.” (page 696)

Assertion 3 – The colossal Olmec heads, which resemble a stereotypical ‘‘Negroid,’’ were carved hundreds of years before the arrival of the presumed models and may have been created before 1100 B.C.

Response 3 – The authors of RNAC are correct that Dr. Van Sertima’s proposed contact between the Olmecs and the Ancient Egyptians was during the 25th Dynasty of Egypt around 800 B.C. to 680 B.C. However, if contact between the Egyptians and Olmecs occurred, one would expect an Egyptian influence on the Olmecs, as Dr. Van Sertima says, and an Olmec influence on the Egyptians, which Dr. Van Sertima does not say.

Evidence of possible Olmec influence on the Egyptians came in 1992, when Dr. Svetla Balabanova, looked at the remains of Pharaoh Ramses II, who reigned from 1279 to 1213 BCE, which is about the time period the RNAC authors say the Olmec heads were created.. Dr. Balabanova analyzed samples from the Pharaoh’s hair, intestinal tract, soft tissue, and bone samples, and found trace amounts of cocaine and nicotine, which are from plants native to the New World that the Egyptians could not have in their systems without contact with the Americas.

While Dr. Balabanova’s research does not prove Ancient Egyptians interacted with the Olmecs, it does show that Egyptians or a trading partner, like the Land of Punt, were in the Americas prior to 1100 B.C.

Assertion 4 – Olmec heads are of indigenous Americans not Africans

• Assertion 4a – Nubians and Egyptians, who come from a desert environment and have long, high noses, do not resemble their supposed “portraits.”

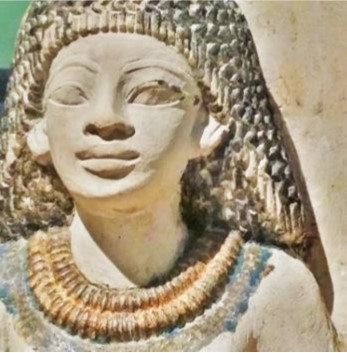

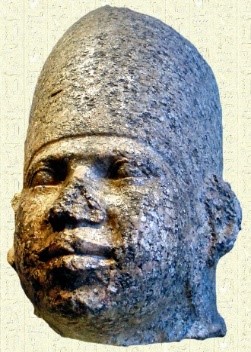

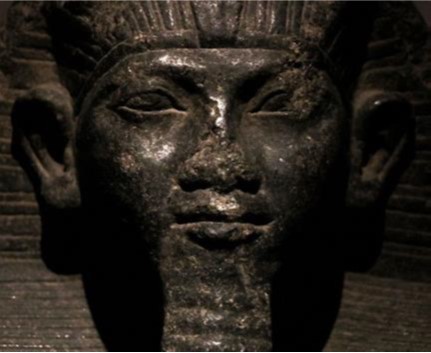

• Response 4a – Below on the left is the bust of Pharaoh Huni of the 3rd Dynasty of ancient Egypt; the bust on the right is Pharaoh Senusret II of the 12th Dynasty of ancient Egypt; and the center picture is the Olmec head used in my Olmec Civilization blog. This shows that not all ancient Egyptians had high noses and some images of ancient Egyptian heads resembled Olmec heads.

• Assertion 4b – Dr. Van Sertima … “places great emphasis on Tres Zapotes head 2 … because it has seven braids dangling from the back, which he claims” … “to be a characteristically Ethiopian hairstyle. … the Olmec braids do not look like either Egyptian or Nubian ones.”

• Response 4b – Braids can be traced back to 3500 B.C. in African culture, have been worn by men and women, and indicate everything from societal status, ethnicity, marital status, religion, and more. Braids can take many forms. It should be noted that in Ancient Egypt, the number seven was a symbol of perfection and efficiency.

• Assertion 4c – Nubians and Egyptians, who come from a desert environment-and have long, high noses, do not resemble their supposed portraits.

• Response 4c –To highlight the inaccuracy of the assertion, I have included, below, images of Nubians with wide noses and thick lips, and one picture, in the center, of the Olmec head used in my Olmec blog. These and other pictures show that not all Nubians had high noses and some Nubian and Egyptian head images resembled the Olmec heads.

|  |  |

| Nubian denizen | Olmec Head | Ancient Egyptian Nubian Art |

Assertion 5 – Claims for the diffusion of pyramid building and mummification are fallacious

• Assertion 5a – Claims of the diffusion of Pyramid Building are fallacious.

• Response 5a – I have read articles about similarities between Olmec and ancient Egyptian pyramids and find the arguments to be complex. However, in 1978 Japanese construction engineers and research scientists from Japan (Nippon Corporation) attempted building a 60-foot-high pyramid using, what were thought to be, ancient Egyptian building techniques. In the end, modern vehicles and machinery were used to move the stones and position the blocks. And, the Japanese team still had difficulties accurately cutting the stones. This means ancient Egyptians and Mesoamericans each had ways to build pyramids that are unknown to us today. While we do not know what the construction methods were, it is easier to imagine ancient Egyptians sharing construction technology with the Olmecs than that each invented a successful technique totally independent of each other when 20th century technology cannot do so today.

• Assertion 5b – Mummification – The Chinchorro mummies are mummified remains of individuals from the South American Chinchorro culture, found in what is now northern Chile. They are the oldest examples of artificially mummified human remains, having been buried up to two thousand years before the Egyptian mummies. The oldest human made Chinchorro mummy dates from around 5050 BCE, which means the mummies are over 7,000 years old.

• Response 5b – A mummy found in Uan Muhuggiag, a place in the central Libyan Sahara, called the Tashwinat Mummy, is around 5,600 years old, dating back to 3600 B.C.E. This chronology means that mummification, like cocaine use, may be an influence of Mesoamericans on ancient Africa. As it predated the Olmec and Egyptian civilizations, it raises interesting questions. This is an area where more research is needed.

Conclusion

Given the above information, most of the evidence in response to the critical RNAC assertions are shown, by sources other than those of Dr. Van Sertima, to support Dr. Van Sertima’s theory that there was contact between the ancient Egyptians and the Olmec civilization.

In addition, some of the cited evidence indicates that some of the details of Dr. Van Sertima’s research and theories may be wrong but that his overall theory, for contact and influences of the ancient Egyptians on the Olmecs, was correct. There is also evidence that the Olmecs had some impact on the Ancient Egyptian civilization. This is what one would expect if contact occurred between the two civilizations.

The above evidence suggests that more, not less, research into the interactions between Africans in general, ancient Egyptians in particular, and Mesoamerican civilizations should be conducted. For example, more research might allow a better understanding of how African cotton arrived in the Americas, the trading relationships that brought cocaine to ancient Egypt, and whether ancient Americans and Africans shared any mummification techniques. But the research is unlikely to bring new insights unless we bring to the research “a fundamentally new vision of history.” A vision that sees blacks not as backward, slow, and a “beggar in the wilderness of history, a menial or an eternal and immutable slave.” Instead, new research must envision blacks as accomplished partners in human history.

My next blog will return to my original schedule of focusing on the Indus Valley Civilization.

George Bustin

Howard Bell